Hip replacement is a medical procedure in which a synthetic implant replaces the hip joint. It is the most successful, least expensive, and least dangerous type of joint replacement surgery. The femoral head was replaced with ivory in the first recorded attempts at hip replacement, and artificial hips became more common in the 1930s. John Charnley's Low Friction Arthroplasty design was the most widely used in the world, and Dr. San Baw pioneered the use of ivory hip prostheses to replace ununited fractures of the neck of the femur.

In 1969, Dr. San Baw presented a paper titled "Ivory hip replacements for ununited fractures of the neck of the femur" at the British Orthopeadic Association conference in London. His patients, ranging in age from 24 to 87, were able to walk, squat, ride a bicycle, and play football a few weeks after their fractured hip bones were replaced with ivory prostheses, resulting in an 88% success rate.

Several evolutionary improvements have been made in the total hip replacement procedure and prosthesis over the last decade, such as ceramic rather than polyethylene, metal-on-metal implants, and bone cement for the femoral component. The most recent advancements are Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS) approaches, which may result in significantly less soft tissue damage and a faster recovery, and computer assisted orthopedic surgery (C.A.O.S). Hip surface replacement (HSR), also known as hip resurfacing, is an alternative to total hip replacement (THR).

It involves amputating the end of the femur and inserting a metal shank into the femur, and replacing the outer surface of the femoral ball with a cylindrical metal cap. Resurfacing preserves bone stock in the event of a revision and has a larger diameter ball and socket structure, lowering the risk of dislocation and improving range of motion.

In age-matched patients, ten-year success rates of hip resurfacing from studies in England are equal to or greater than standard total hip replacement. Before undergoing hip replacement surgery, patients should be aware of all surgical options and use a variety of surgical techniques.

Hip replacement is a medical procedure in which a synthetic implant replaces the hip joint. It is the most successful, least expensive, and least dangerous type of joint replacement surgery. The femoral head was replaced with ivory in the first recorded attempts at hip replacement, which were performed in Germany.

In the 1930s, the use of artificial hips became more common; the artificial joints were made of steel or chrome. They were thought to be superior to arthritis, but they had a number of drawbacks. The main issue was that the articulating surfaces could not be lubricated by the body, which caused wear and loosening and necessitated the replacement of the joint (known as revision operations).

Teflon attempts resulted in joints that caused osteolysis and wore out within two years. Infection was another major issue. Prior to the discovery of antibiotics, joint surgery carried a high risk of infection. Even with antibiotics, infection is still a factor in some revision surgeries. These infections are not always the result of surgery; they can also occur as a result of bacteria entering the bloodstream during dental treatment.

John Charnley's work at the Manchester Royal Infirmary in the field of tribology resulted in a design that completely replaced the other designs by the 1970s. Charnley's design consisted of three parts: (1) a metal (originally Stainless Steel) femoral component, (2) an Ultra high molecular weight polyethylene acetabular component, and (3) special bone cement. Synovial fluid was used to lubricate the replacement joint, which was known as the Low Friction Arthroplasty.

The small femoral head (22.25mm) caused wear issues, making it only suitable for sedentary patients, but a significant reduction in resulting friction led to excellent clinical results. For more than two decades, the Charnley Low Friction Arthroplasty design was the most widely used in the world, far outpacing the other options (like McKee and Ring).

Dr. San Baw (29 June 1922 - 7 December 1984), a Burmese orthopaedic surgeon, pioneered the use of ivory hip prostheses to replace ununited fractures of the neck of the femur ('hip bones'), when he first used an ivory prosthesis to replace the fractured hip bone of an 83-year-old Burmese Buddhist nun, Daw Punya. Dr. San Baw was the chief of orthopaedic surgery at Mandalay General Hospital in Mandalay, Burma. From the 1960s to the 1980s, Dr. San Baw used over 300 ivory hip replacements.

In September 1969, he presented a paper titled "Ivory hip replacements for ununited fractures of the neck of the femur" at the British Orthopeadic Association conference in London. Dr. San Baw's patients, ranging in age from 24 to 87, were able to walk, squat, ride a bicycle, and play football a few weeks after their fractured hip bones were replaced with ivory prostheses, resulting in an 88% success rate. Dr. San Baw's use of ivory was cheaper than metal, at least in Burma during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s (before the illicit ivory trade became rampant in the early 1990s).

Furthermore, it was discovered that there was a better 'biological bonding' of ivory with the human tissues nearby the ivory prostheses due to the physical, mechanical, chemical, and biological qualities of ivory. An excerpt from Dr. San Baw's paper, which he presented at the British Orthopaedic Association's Conference in 1969, appears in the February 1970 issue of the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British edition).

Several evolutionary improvements have been made in the total hip replacement procedure and prosthesis over the last decade. Many hip implants are made of ceramic rather than polyethylene, which according to some research significantly reduces joint wear. Metal-on-metal implants are also becoming more popular. Some implants are joined without the use of cement; the prosthesis is given a porous texture to encourage bone growth. This has been shown to reduce the need for acetabular component revision. However, after 35 years of clinical experience, surgeons still frequently use bone cement for the femoral component, which has proven to be very successful.

The most recent advancements are several competing Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS) approaches, which may result in significantly less soft tissue damage and a faster recovery. The implant manufacturers are also heavily marketing C.A.O.S (computer assisted orthopedic surgery), despite the fact that its value is largely unproven. Computer-assisted surgery is said to make prosthetic implantation easier.

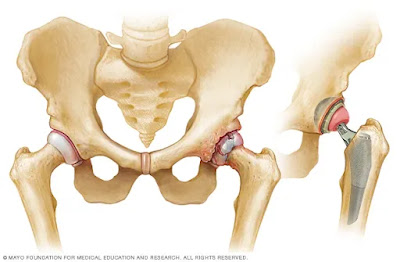

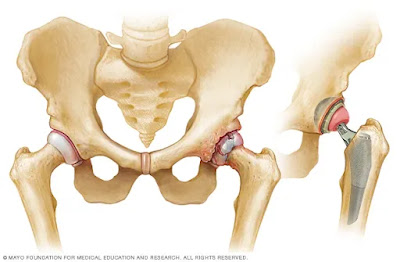

Hip surface replacement (HSR), also known as hip resurfacing, is an alternative to total hip replacement (THR). A prosthetic socket is pressed into the pelvis with both THR and HSR. THR involves amputating the end of the femur, inserting a metal shank into the femur, and the shank holding a ball that mates with the socket. The end of the femur is not amputated during resurfacing; instead, the outer surface of the femoral ball is replaced with a cylindrical metal cap. The common THR problem of the metal shaft loosening from the femur is eliminated by resurfacing.

Resurfacing preserves bone stock in the event that a revision is required. A larger diameter ball and socket structure more closely resembles the natural joint structure, lowering the risk of dislocation and improving range of motion. There is no published clinical evidence that today's CoCr metal-on-metal articulating surfaces have the same osteolytic effect on bone as older polyethylene devices. In age-matched patients, ten-year success rates of hip resurfacing from studies in England are equal to or greater than standard total hip replacement. The first modern resurfacing device was approved by the FDA in the United States in May 2006, and approximately 90,000 resurfacings have been performed worldwide.

Before undergoing hip replacement surgery, patients should be aware of all surgical options. Hip surgeons use a variety of surgical techniques and achieve varying results. There are currently several incisions used to access your hip joint. The posterior approach (used by the vast majority of orthopedic surgeons) separates the gluteus maximus muscle in line with the muscle fibers to gain access to the hip joint. Other methods gain access to the hip joint from the lateral side. Unlike the posterior and lateral approaches, the anterior approach uses a natural gap between soft tissues to gain access to the hip joint. Its main drawbacks are that it risks damaging the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve and that it is not widely available to the general public because fewer surgeons have been trained in this technique.